There is a whole industry dedicated to studying hedge funds’ past purchases in an attempt to extract some alpha. Once a quarter, all institutional investors with over $100mm under management are required to report their long positions – the so called Form 13F is filed within 45 days of the end of a calendar quarter. Basically, 13F is a look at what hedge funds bought and sold 45 days or more ago.

This morning, I was going through Josh Brown’s links and clicked on a piece from FactSet, covering hedge funds’ moves from Q3. I saw that the two largest individual stock additions in that quarter were Facebook ($FB) and Baidu ($BIDU) and tweeted the following:

ivanhoff

Nov. 22 at 9:28 AM

We certainly did not need to wait a few months to figure out that $FB and $BIDU were under heavy accumulation during the summer. Price action on those names told use everything we had to know, in real time.

Don’t get me wrong – there are many strategies that try to piggy-back some of the famous money managers positions. Some are doing an exceptional job by copying and following. From my perspective, 13Fs have more educational than actionable value. 13Fs could help you figure out how investors think and when they buy and sell. In the case of $FB and $BIDU in Q3, there are three main observations that could be made:

1) Buying highly shorted stocks after they crush earnings estimates and gap to new all-time highs.

2) Pay attention to industry relative strength – anything related to social media and internet was melting hot during the summer.

3) When institutions buy, they leave traces. They don’t do all their buying in one day, therefore there’s plenty of time for anyone who is watchful enough to jump back with them in real time.

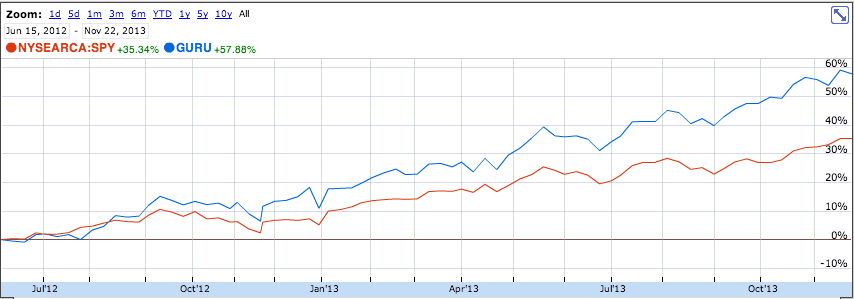

A minute after my tweet, my friend Frank Zorrilla (@zortrades) reminded me that there’s an ETF ($GURU) that buys what select hedge funds bought last quarter and it has been delivering some solid alpha since inception. Look at the chart below

How is that outperformance possible when the media has constantly bombarded us with proves that cumulatively, hedge funds have not really generated any alpha after fees over the past decade? How is it possible for an ETF that buys weeks and months after the tracked hedge funds bought, to outperform the S&P 500. I have no idea what the actual performance of the tracked hedge funds is, but here’s why this ETF might have done so well lately.

1) it tracks mainly hedge funds, which average holding period is more than a year

2) it charges relatively smaller fee of 75bps. Hedge funds charge 2% and 20%. This is a huge difference. If a hedge fund makes 40% pre-fees, after 2/20 its return will be a little less than 30%.

Take into account that this ETF is relatively young and has only operated in a scorching hot bull market. Typically, the success rate of all market strategies is cyclical.