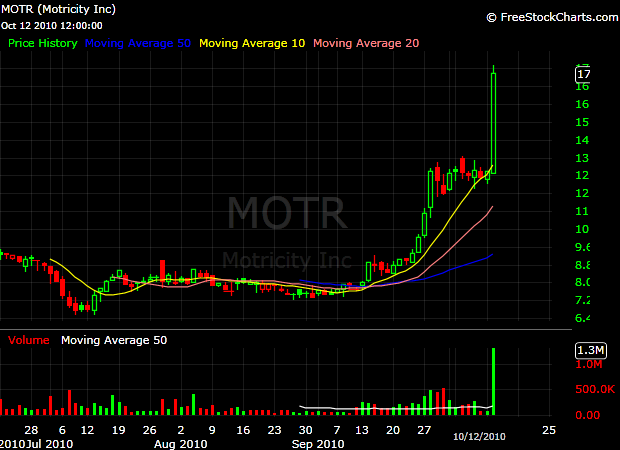

Today one of the suggested traders on StockTwits – @johnsontrading made a very good comment on the price/volume action in $MOTR:

$MOTR – it can pay to not be too strict with volume criteria as often vol shows up when you need it – 61k shares trade yest and 820k today, Oct. 12 at 2:45 PM

Most of us are applying a minimum average daily volume filter in our screens and are missing on some the most furious, short-term moves. When we created StockTwits 50, liquidity was an important criteria and it still is. The reasoning beside that decision is very simple – low liquidity creates higher volatility, it makes accumulation difficult and flawless exits close to impossible. In the same time, we understand the impact that a new catalyst could cause to a stock’s average daily traded volume and this is reflected in the ST50 algorithm.

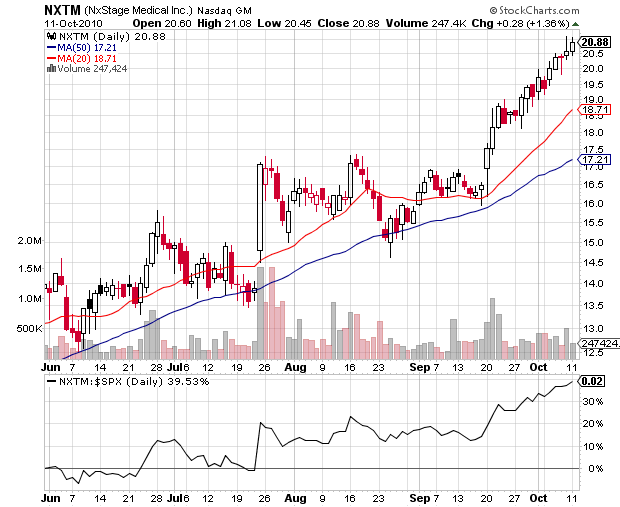

Let’s go back in time and take a look at the price/volume action in $OPEN. On February 9th, Open Table Inc. reported a quarterly EPS of $0.14 vs consensus estimate of $0.07. The Y/Y revenue growth was 32%.

Before the report, the average daily volume in $OPEN was about 100k

A month after the report, the averege volume increased to 200k

Today, 9 months later, the average daily volume is 400k

Liquidity tends to follow price, when there is a sustainable catalyst behind the move.