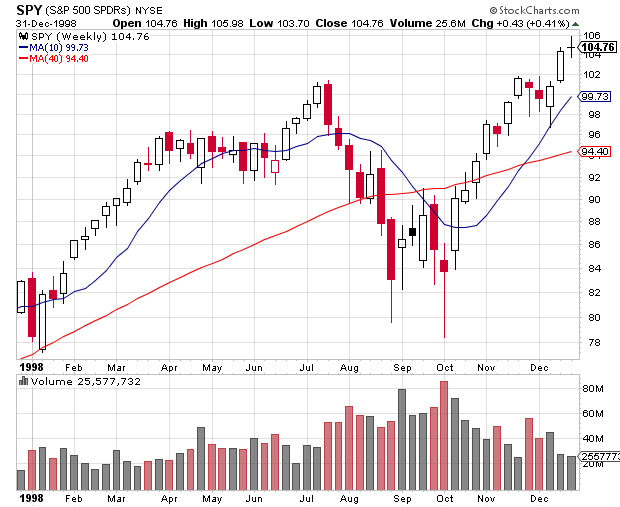

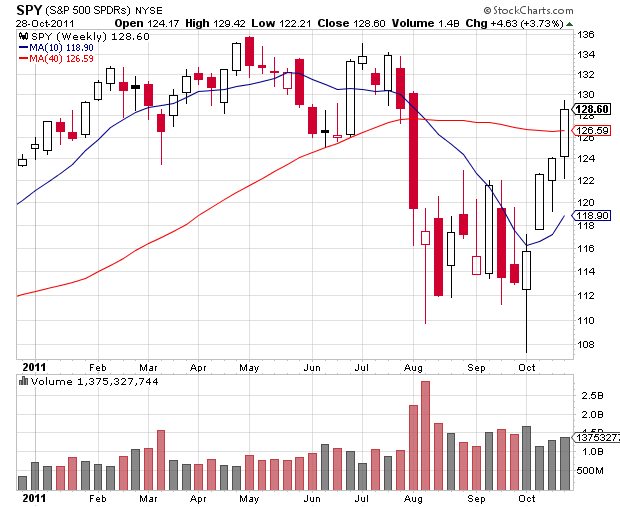

History never repeats, but it often rhymes, at least from psychological perspective. One cannot help but ponder the similarities between 1998 and 2011. In the Summer of 1998, stock markets across the world sold off because of the Asian credit crisis. In the summer of 2011, the sell-off was caused by European credit crisis. Of course, the magnitude of the problem today is much bigger and complicated, but the governmental bodies across the world are willing to take desperate measures and do anything to somehow solve the problem or at least postpone it for as long as possible.

2011 and 1998 have similarities from technical perspective too: major low in August that was penetrated intraday in October, only for the market to snap back and rally 20% in 4 weeks after that.

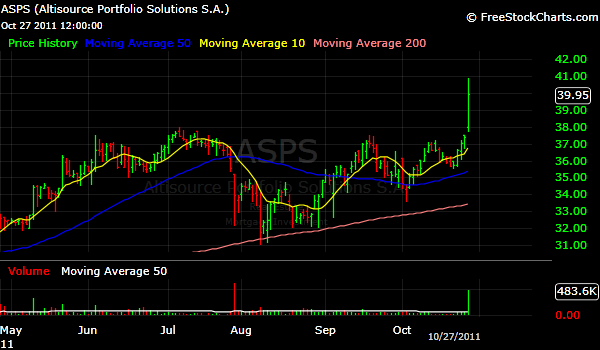

I am not suggesting in any way that 2011 will be exactly like 1998, but I remain open minded for the possibility. As a matter of fact, I think the markets are overextended here and a consolidation of some sort next week is very high probability. $TZA seems like a good hedge/pick for the next few days. Other than that, the market looks higher for the rest of the year, baring any unforeseen event.

Of course, I will trade what I see, not what I think and I will change my mind if the market tells me to.