They say that marines do more before 9am than most people do all day. Josh Brown is one of those persevering pros who do more than the marines. His first book, Backstage Wall Street, is a well thought out mix of hard-earned personal experience from both the buy and sell side of the business, in-depth research and witty commentary on the side effects of greed and fear on Wall Street. Backstage Wall Steet is Liar’s Poker meets Kung Fu Panda. Without any hesitation, I would label it as a highly useful read for anyone that manages or intends to manage money.

Here are some of the insights I picked up from reading it:

1. Selling one’s expertise is much easier than actually developing an expertise, especially as it pertains to investing.

2. A good broker can close on anyone and he means anyone. Well almost. I was secretly hoping to adopt some of the successful selling techniques in my portfolio of bar pick up lines, but then Brown slapped me with the following: “It is nearly impossible to impulse-sell securities to women, as they tend to invest more for financial security than for bragging rights, big fish tales, or naked greed like wealthy men do.” If only stocks were shoes.

3. By driving the costs out of trading, the online brokerages had inadvertently driven the investment banks back to the profit drawing board—as history has shown time and again, Wall Street getting creative is almost never a good thing.

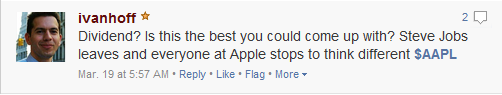

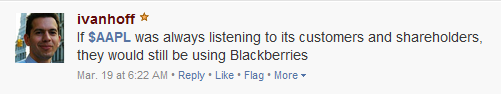

4. Social media is just one more disruptive force that allows talented individuals to build their own brands and to gnaw away at the once-mighty oaks that have ruled the industry for so long.

5. Wall Street Sell-side research is a giant joke. In bull markets, you don’t need them because everything goes up. In bear markets, their warning is usually way after the fact.

6. The game used to be played like this: “Do your initial public offering through our banking department, and our brokerage analysts will guarantee you a ‘strong buy’ rating for your first six months of trading.”

7. There is still an understanding that you don’t downgrade the big clients of the firm. When analysts do downgrade stocks, in my experience, it tends to come only after a slew of weak earnings reports and in the context of a stock price that has already been falling for months. In fact, ask most experienced traders about which type of sell-side call gets them most excited and they’ll almost unanimously answer that they love when a broker goes negative. The value investors will wholeheartedly agree.

8. The most effective method of selling anything in this world is through storytelling. And it is not just product that needs to be sold. Strategies have received their own stories as well. “Buy and hold” is one of the greatest stories ever told, this despite the fact that in the past century we’ve seen 25 cyclical bear markets and two bone-crushing secular bear markets.

9. There are a lot of “murderholes” on Wall Street: SPACs, Chinese ADRS, one-drug biotechs, private placements among others. I love the quote from Mike Tyson in the book: ““Everyone has a plan, ’til they get punched in the mouth.”

Source: Brown, Joshua M. (2012-02-29). Backstage Wall Street: An Insider’s Guide to Knowing Who to Trust, Who to Run From, and How to Maximize Your Investments. McGraw-Hill.