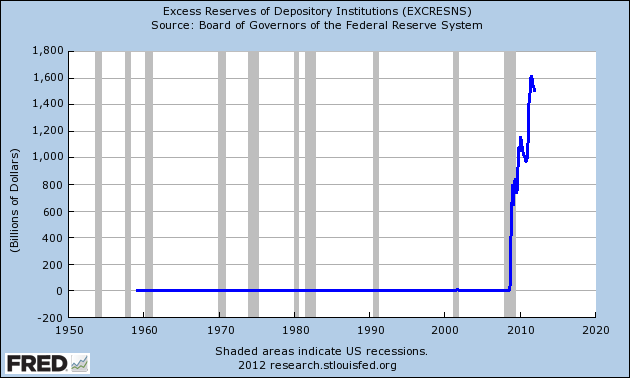

It is a public secret that Fed’s attempt to sustain interbanking lending during the last financial crisis has led to ginormous increase to gynormous increase in banks’ excess reserves (the a part of capital above the minimum required reserves that it is not loaned). At the beginning of 2007, the excess reserves in the U.S. financial system were $1.5 billion. Today, they stay at $1.5 trillion – a 1000-fold increase in 4 years.

Banks have three major options to allocate those excess reserves:

– keep them and continue to receive money from the FED. Yes, they are getting paid for money they initially received from the FED and they are getting paid well: 0.25% compared to 0.21% for 2yr treasury notes and 0.03% for 3-month notes;

– buy short-term U.S. Treasuries and earn interest, which at this point is close to zero;

– lend it to the private sector at higher interest rates.

In normal circumstances, all banks would choose option number three, because it is the most lucrative for them. The thing is that the circumstances are not normal and there simply isn’t demand for this money at this point of time, so banks keep hoarding and earning the little percentage that the Fed and Treasuries pay them.

The exorbinant amount of excess reserves has many people worried that once demand for leverage from the private sector picks up, the final result will be accelerating inflation that the Fed won’t be able to stop. It turns out that one of Fed’s plans to fight this potential development is through raising the interest it pays for excess reserves in order to discourage banks from further lending. I am curious to see how this will work out.

Anyway, it looks like that the shortest way to rising profits for the banks is rising inflation expectations, which should encourage loan demand. Maybe this is one of the explanations behind the recent appreciation in U.S banks’ stocks. It is not only a result of short squeeze and “January effect”.

Todd Keister and James McAndrew from the NY Fed explain in details how everything works. I encourage you to read their paper from the summer of 2009 in its entirety in order to get better understanding of the mechanism of the U.S financial systems and the potential consequences for the future.

When the economy begins to recover, firms will have more profitable opportunities to invest, increasing their demands for bank loans. Consequently, banks will be presented with more lending opportunities that are profitable at the current level of interest rates. As banks lend more, new deposits will be created and the general level of economic activity will increase. Left unchecked, this growth in lending and economic activity may generate inflationary pressures. Under a traditional operating framework, where no interest is paid on reserves, the central bank must remove nearly all of the excess reserves from the banking system in order to arrest this process. Only by removing these excess reserves can the central bank limit banks’ willingness to lend to firms and households and cause short-term interest rates to rise.

Paying interest on reserves breaks this link between the quantity of reserves and banks’ willingness to lend. By raising the interest rate paid on reserves, the central bank can increase market interest rates and slow the growth of bank lending and economic activity without changing the quantity of reserves. In other words, paying interest on reserves allows the central bank to follow a path for short-term interest rates that is independent of the level of reserves. By choosing this path appropriately, the central bank can guard against inflationary pressures even if financial conditions lead it to maintain a high level of excess reserves.

This logic applies equally well when financial conditions are normal. A central bank may choose to maintain a high level of reserve balances in normal times because doing so offers some important advantages, particularly regarding the operation of the payments system. For example, when banks hold more reserves they tend to rely less on daylight credit from the central bank for payments purposes. They also tend to send payments earlier in the day, on average, which reduces the likelihood of a significant operational disruption or of gridlock in the payments system. To capture these benefits, a central bank may choose to create a high level of reserves as a part of its normal operations, again using the interest rate it pays on reserves to influence market interest rates.

Source: NY Fed

2 thoughts on “Banks Need Higher Interest Rates to Start Making Money”

Comments are closed.