The options world is multidimensional and it offers countless ways to implement a trading idea. In this post, I look at debit and credit spreads. Spreads are directional strategies with limited reward and limited risk.

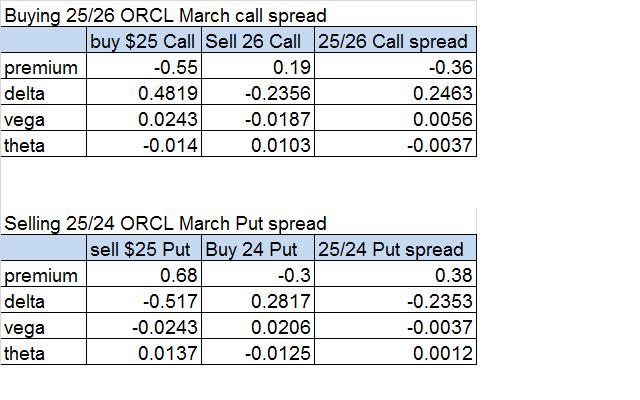

A typical debit spread is long ORCL 25/26 March Call spread. In this case, you are buying the $25 ORCL March Call and simultaneously sell $26 ORCL March Call against it, to decrease the paid premium. The maximum risk is the paid premium. The maximum reward is the difference between the spread (in this case $1) and the paid premium. The main purpose of buying premium via a debit spread is to establish a directional trade and minimize the negative effects of IV and time.

A typical credit spread is short ORCL 25/24 March Put spread. Here we sell a higher strike put to collect the premium and use part of the proceeds to buy a lower strike put, which role is to hedge against unexpected strong decline in the stock. The maximum that we could make is the collected premium if ORCL remains above 25 at expiration date. The maximum we could lose is the difference between the spread of the two strikes and the received premium (in this case: 1 – .38 = .62 if ORCL closes below $24 at expiration date; see the table below). The main purpose of initiating a credit spread is to establish a directional trade and to get the needed leverage with limited risk. A secondary purpose is to utilize the positive effects of IV and theta.

Let assume that for some reason you are slightly bullish on ORCL for the next 2-3 weeks. By slightly bullish I mean an expectation of a 2-5% move. At the moment of writing, ORCL is traded for $24.82. Let analyze the elements that will impact the premium of ORCL 25/26 March call and ORCL 25/24 put:

What would be the impact on each of the positions if in the next 5 days ORCL goes up $1 to 25.82 and the IV of the contracts decline by 4 percentage points to 20?

In the 25/26 March call spread, the impact of delta would be a gain of $0.2463 per share, the impact of vega will be a loss of (-4)*0.0056 = -$0.0224; the impact of theta will be a loss of 5*(-.0037) = -$0.0185. The overall change in the position is expected to be a gain of $0.2054 or 56% above the base of .36 that we paid. You can see that the effect of vega and theta is minimal in this case and delta is the main driver of profit.

Buying premium by going long a spread reduces the impact of time, but doesn’t eliminate it. In the example, we bought a lower strike call and sold against it a higher strike call in order to minimize the impact of vega and theta. We purchased a spread that is slightly OTM. In order for us to make money, ORCL needs to start moving up and to do it fast, because the more the expiration date approaches, the bigger the negative impact of theta becomes. This is one of the main reasons why I prefer to use short-term spreads to sell premium.

One alternative of going long ORCL via a spread is by selling a put spread for a premium. We don’t have to wait until expiration in order to collect our gain. As the time passes, ORCL price rises and if IV declines, the premium for the 25/24 put will decline and we could purchase it back at a lower price and keep the difference. Let refer to the example.

What will be the change in the 25/24 ORCL March Put spread if the stock goes up $1 in the next 5 days and the IV drops 4 percentage points? The premium will drop – $0.2353 due to delta; 4*(-.0037) = – $0.0148 due to vega; 5*(-.0012) = -$0.006 due to theta. The overall decline will be – $0.2561, which means that the 25/24 ORCL March Put spread will trade for (.38 – .2561) = $.1239. We could purchase it back to offset our position and keep the difference of almost 26 cents per share.

You could see in this example that the effect of theta and vega was relatively small compared to the effect of delta. What does it mean? To make money trading spreads, you need the underlying stock to move in the expected direction and to do it quickly. You need to pay attention to IV. The simple rule to buy short-term premium when you expect the IV to increase is valid here also. Just to remind you, IV tends to rise in expectations of a major event such as an earnings report or when the underlying stock is rapidly declining. Here is a snapshot of ORCL IV:

The chart is courtesy of OX

As a general rule, when volatility is high, options tend to sell at a premium, when low, options tend to sell at a discount. In an effort to trade options successfully, it is important to understand their relative price history. We don’t only want to know if the IV is historically low or high, but also and more importantly if the IV is rising or declining and how far it is likely to go.

ORCL is scheduled to report earnings on March 17th, AMC. As this date is approaching the IV is likely to rise.

After Implied Volatility, the most misunderstood and underestimated topic in the options world is liquidity. There are about 100 stocks and indexes, which options contracts are liquid enough to be traded profitably. Many options traders lose the battle before it even begins. At the moment you get filled on an options spread, you are in a losing position. You paid a commission to your broker. In the case of a bull call spread, you most likely paid the offer price for your long call and you got the bid price for your short call with higher strike. The lack of sufficient liquidity will put the trader of OTM options and spreads at a huge disadvantage. Not all options are liquid enough to be considered for a trade. In a future post I will come up with a list, revealing stocks, indexes and ETFs which options posses the needed liquidity.

To summarize, it makes sense to buy premium via vertical spreads when:

1) You expect a certain stock to gradually increase or decline in value in the following 3 to 6 months.

2) You want to minimize the effect of IV and theta. You rely exclusively on the move of the underlying stock in order to profit

3) You don’t want to allocate too much capital on this particular trading idea and you don’t want to overpay in terms of risk and time premium.

4) The options contracts of the stock/index you like are highly liquid, therefore you could easily get in and out without losing too much on the difference between the ask and the bid for your contract.

5) The purchased vertical offers at least 3:1 reward to risk. A good example would be buying A three month 40/45 call spread for a debit of 1.20. In this case, your maximum loss is 1.20. Maximum gain is 3.80.

6) Don’t risk more than 1% of your trading capital on any vertical trade. This means that if your capital is 100k and the premium of the debit spread you are looking at is $2, you cannot afford to buy more than 5 contracts.

It makes sense to sell premium via vertical spreads when:

1) you have directional bias for the next few weeks

2) the IV is high and you expect it to decline.

3) You want to profit from theta. With each day, theta will add a little to your position. This is why I mentioned that mainly short-term credit spreads should be considered: 10-15 days before expiration, when the wasting effect of theta is the biggest and it is increasing exponentially.

4) It is preferable to sell OTM credit spreads, because they carry the most time value and therefore will erode more quickly.

5) Don’t risk more than 1% of your trading capital. If you are currently working with 100k and the premium of a $5 spread you like to sell is $2, you cant afford to sell more than 3 contracts. (1% of 100k is 1000 and $3 is your maximum risk per share)

Unfortunately, this post turned out to be too long for my taste, but I couldn’t make it any shorter without missing some essential points. In the next post, I will share my thoughts on Selling premium – dressed and naked. The first should become one of the favorite strategies of long-term investors, the second is a favorite strategy of many hedge funds.