James Mai is one of the founders of Cornwall Capital. His fund was featured in Michael Lewis’s The Big Short book as one the organizations that made a fortune during the subprime crisis. Cornwall Capital was started in 2002 and it has netted 40% per year.

Cornwall Capital seeks highly asymmetric trades where the potential reward is multiple times bigger than the risk taken. They often buy long-term (1-2-year) out of the money options to take advantage of special situations that are underpriced by the options market. This strategy sounds similar to what Jim Leitner does.

Markets tend to over-discount known risks which create amazing long-term opportunities

Markets tend to overdiscount the uncertainty related to identified risks. Conversely, markets tend to underdiscount risks that have not yet been expressly identified. Whenever the market is pointing at something and saying this is a risk to be concerned about, in my experience, most of the time, the risk ends up being not as bad as the market anticipated.

Option markets tend to assign a normal distribution to almost everything. This makes paying for a long-term gamma extremely cheap in some situations. I covered Scott Bessent who talks about that as well.

We had already seen cases where the option market assigned normal probability distributions to situations that clearly had bimodal outcomes.

The first thing we checked was whether the Altria options still assumed a normal probability distribution, despite the presence of a bimodal event. Sure enough, the Altria option prices still implied a normal distribution, which meant the out-of-the-money options were way too cheap. Since our work suggested a greater likelihood for a bullish outcome, we bought the out-of-the-money calls. The calls appreciated sharply when one of the key cases supporting the rating downgrades was thrown out on appeal shortly after we initiated our investment. We made about 2.5 times our money on the trade. Although we made a large return for a short holding period, in hindsight, we sold far too soon.

Options are priced lowest when recent volatility has been very low. In my experience, however, the single best predictor of future increases of volatility is low historical volatility. When volatility gets very low in a market, we consider that a very interesting time to start looking for ways to get long volatility.

Often, the longer the duration of the option, the lower the implied volatility, which makes absolutely no sense. We recently bought far out-of-the-money 10-year call options on the Dow as an inflation hedge. Implied volatility on the index is very low. The Dow companies would be in the best position to pass along higher prices. There is also an interest rate bet implicit in buying long-term options that can be quite interesting when interest rates are very low, as they are now. By being long 10-year call options, we are taking exposure on the risk-free rate implicit in the option pricing models. If interest rates go up, the value of the options can go up dramatically.

Option models generally assume that forward prices are predictive of the future movements in the spot price. Academic research and common sense suggest that this relationship is often invalid.

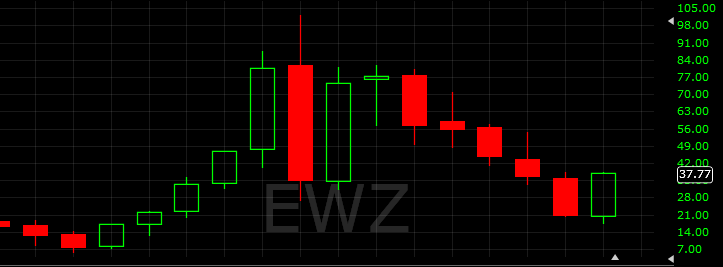

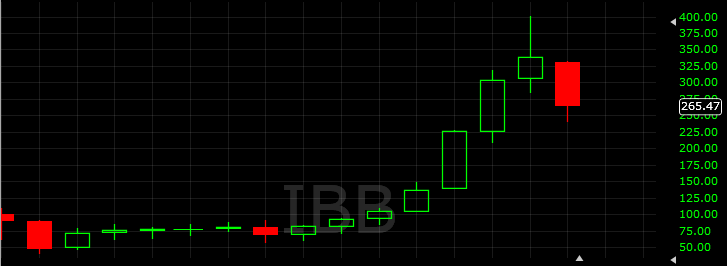

The best performing stocks in the first stage of a market recovery are usually the ones that were hit the hardest during a correction.

The low-quality names tend to outperform early in the cycle, and the high-quality names tend to outperform toward the end of the cycle.

Why the so-called boring businesses with low, but steady growth tend to do very well long-term

Beta is measured based on daily relative price changes, which can be a very poor indicator of long-term relative price changes.

Volatility is a terrible proxy for measuring potential price change over longer intervals of time. For example, if an asset price changes by a constant percentage each day, its volatility will be zero. One of our strategies is called cheap sigma and is predicated on the idea that markets sometimes trend and that volatility will dramatically understate the potential price move of markets that trend.

The trend is your friend if you want to be a buyer of premium.

Option prices will tend to be priced too low in smoothly trending markets.

Option math works a lot better over short intervals. Once you extend the time horizon, all sorts of exogenous variables are introduced that can throw a wrench into the option-pricing model.

Great setups don’t come up that often

The reality is that we have a business model in which we dig 50 dry wells for every idea we explore that leads to a trade in which we find conviction.

We are comfortable losing 100 percent of our premium four times in a row, as long as we believe that a 25-times payout is likely to occur if we make the same bet 10 times consecutively.

Source: Schwager, Jack D. (2012-04-25). Hedge Fund Market Wizards. John Wiley and Sons. Kindle Edition.